When your prescription runs out and the pharmacy says they can’t refill it-not because you forgot to call, but because the drug simply isn’t available-that’s not a glitch. It’s a systemic crisis. In 2025, over 250 essential medications remain in short supply across the U.S., from life-saving antibiotics to chemotherapy drugs and even basic IV fluids. This isn’t just inconvenient. It’s dangerous. Health systems aren’t waiting for the market to fix itself. They’re rebuilding how they get drugs from factory to patient, and the changes are happening fast.

Why Drug Shortages Keep Happening

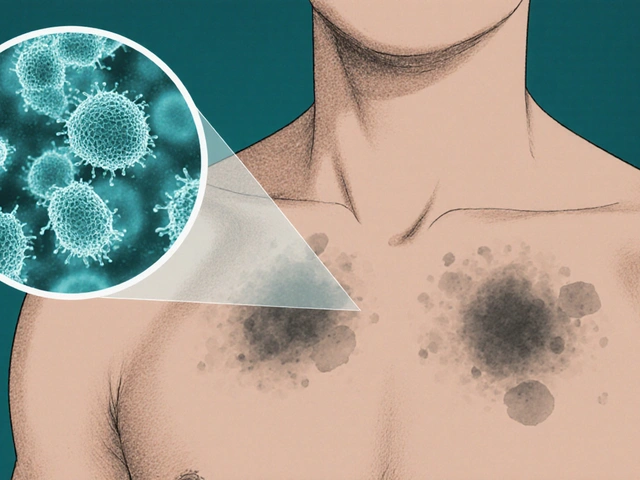

Drug shortages aren’t random. They’re the result of broken supply chains, single-source manufacturing, and low profit margins. About 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients come from just two countries: India and China. When a factory there shuts down for inspection, or a natural disaster hits, or a company decides it’s not profitable to make a $0.10 pill anymore, the ripple effect hits hospitals weeks later.

Some drugs are made by only one company. If that company faces quality control issues-like the 2023 FDA shutdown of a major sterile injectable plant in Puerto Rico-hospitals scramble. Cancer centers lost access to doxorubicin. NICUs ran out of phenobarbital. Emergency rooms had to delay antibiotics. These aren’t hypotheticals. These are real events that happened in 2024 and 2025.

Real-Time Inventory Tracking

Health systems used to rely on paper logs and phone calls between pharmacies and distributors. Now, 67% of large hospitals use real-time digital inventory platforms that track drug levels down to the vial. These systems connect directly to suppliers and flag low stock before it becomes a crisis.

For example, Mayo Clinic’s automated inventory system now alerts pharmacists when a drug drops below a 14-day supply threshold. It doesn’t just say “low stock.” It recommends alternatives, suggests reorder quantities based on historical usage, and even auto-generates purchase orders. The result? A 41% reduction in critical drug shortages at their 14 hospitals in 2024.

Alternative Sourcing and Bulk Purchasing

When one supplier fails, health systems no longer wait. They’ve formed buying coalitions. In 2024, over 200 U.S. hospitals joined the HealthTrust Purchasing Group to pool demand for high-risk drugs. By buying in bulk together, they get better pricing and guaranteed allocation from manufacturers.

Some systems are going further. Kaiser Permanente now maintains strategic stockpiles of 12 critical drugs that have historically been in short supply. These aren’t just extra boxes in a warehouse. They’re rotated quarterly, tested for potency, and backed by FDA-approved alternate manufacturers. They’ve also signed long-term contracts with secondary suppliers in Europe and Canada, bypassing the U.S. middlemen who often delay shipments.

Substitution Protocols and Clinical Guidelines

Not every drug has a direct substitute. But many do. The challenge? Clinicians don’t always know which ones are safe to use instead.

Health systems are now creating dynamic, evidence-based substitution guides. Johns Hopkins launched a digital tool in early 2025 that shows doctors real-time alternatives when a drug is unavailable. It doesn’t just list options. It ranks them by clinical equivalence, patient risk, and cost. For instance, if vancomycin is out, the system shows: “Ceftaroline (Tier 1, equivalent efficacy, 12% higher cost) - preferred for MRSA.”

Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committees now meet weekly to review shortages and update protocols. Nurses and pharmacists are trained to flag potential substitutions before prescriptions are even written. This isn’t guesswork. It’s protocol-driven decision-making backed by clinical trials and FDA guidance.

Manufacturing Partnerships and Vertical Integration

Some health systems are no longer just buyers-they’re makers. In 2024, the Cleveland Clinic opened its own sterile compounding facility to produce high-demand injectables like epinephrine and lidocaine. It’s not cheap. It cost $42 million. But it cut their reliance on external suppliers by 63% for those drugs.

Similarly, Intermountain Healthcare partnered with a U.S.-based generic manufacturer to co-develop a stable version of a commonly短缺ed chemotherapy drug. They shared R&D costs and got exclusive distribution rights for 18 months. The result? A drug that was unavailable for 11 months in 2023 is now reliably stocked at 98% of their clinics.

This trend is growing. The FDA has fast-tracked 17 applications from health systems seeking to become licensed manufacturers since 2022. The goal? Reduce dependence on overseas production and build resilience from within.

Regulatory Flexibility and Emergency Waivers

The FDA has become more responsive. In 2024, they expanded the Drug Shortage Program to allow temporary importation of drugs from approved international sources-even if those drugs aren’t FDA-approved for sale in the U.S., as long as they meet WHO standards.

Hospitals can now apply for emergency waivers to use non-U.S. versions of critical drugs. For example, during a shortage of the antibiotic meropenem, several hospitals in Texas received shipments of the same drug manufactured in Germany under EU GMP standards. The FDA reviewed batch records, approved use under emergency protocols, and monitored outcomes. No safety incidents were reported.

This flexibility is now baked into emergency response plans. Every major health system has a designated team trained to submit these requests within 24 hours of a shortage declaration.

Technology and Automation

AI isn’t just for chatbots anymore. It’s being used to predict shortages before they happen. Health systems are feeding data into machine learning models: global shipping delays, raw material prices, manufacturer recall history, weather patterns in manufacturing regions, even political instability in key countries.

One model developed by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) predicted a 92% chance of a phenylephrine shortage three weeks before the FDA announced it. They ordered extra stock, switched to alternatives in protocols, and avoided patient delays.

Robotic dispensing systems are also helping. At Boston Medical Center, automated robots now pull and package drugs with built-in shortage alerts. If a drug is flagged as low, the robot skips it and substitutes the next approved option-without needing a human to intervene.

What’s Still Broken

Despite all this, 58% of pharmacists still report at least one critical drug shortage per week, according to the 2025 National Association of Chain Drug Stores survey. The biggest gaps remain in older, low-margin drugs-like corticosteroids, anticonvulsants, and generic antibiotics. These aren’t profitable for manufacturers, so they’re the first to disappear.

Small rural hospitals still struggle. They don’t have the staff to monitor inventory daily. They don’t have the clout to join buying coalitions. And they can’t afford AI tools or in-house manufacturing.

There’s also a lack of transparency. Manufacturers aren’t required to give advance notice of production halts. A company can shut down a line on Monday and not tell the FDA until Friday. By then, hospitals are already out of stock.

The Path Forward

The most successful health systems are no longer just reacting-they’re redesigning the system. They’re combining real-time tracking, local manufacturing, AI forecasting, and policy advocacy. They’re pushing Congress to pass the Drug Supply Chain Security Act reforms that would require manufacturers to give 6-month notice before discontinuing a drug.

They’re also lobbying for incentives to bring generic drug production back to the U.S. and Canada. The Inflation Reduction Act’s new manufacturing tax credits are starting to show results. Two new U.S.-based sterile injectable plants broke ground in 2024, with more planned for 2026.

But the real change is cultural. Pharmacists are no longer seen as order-takers. They’re frontline risk managers. Clinicians are trained to think in alternatives. Administrators are budgeting for redundancy, not just efficiency.

Drug shortages won’t disappear overnight. But the days of hospitals hoping for the best are over. The systems that survive are the ones that plan like they’re preparing for war-because, in many ways, they are.

Why are drug shortages getting worse?

Drug shortages are worsening because global supply chains are fragile, manufacturing is concentrated in just a few countries, and many essential drugs are low-profit products that manufacturers don’t prioritize. When a factory shuts down or a supplier stops making a drug because it’s not profitable, there’s often no backup. The system was built for efficiency, not resilience.

Can hospitals make their own drugs to avoid shortages?

Yes, some can-and many are. Hospitals like Cleveland Clinic and Intermountain Healthcare have built in-house compounding facilities to produce critical injectables like epinephrine, lidocaine, and heparin. These aren’t new drugs, but they’re made under strict FDA guidelines. It’s expensive upfront, but it cuts dependence on unreliable suppliers and ensures consistent supply.

Are generic drugs more likely to be in short supply?

Yes. Generic drugs, especially older ones with low profit margins, are the most vulnerable. They’re often made by just one or two manufacturers. If one fails, there’s no competition to fill the gap. Antibiotics, chemotherapy agents, and IV fluids are common examples. Brand-name drugs rarely短缺 because companies protect their profits with multiple suppliers and stockpiles.

What can patients do if their medication is unavailable?

Patients should never stop taking a medication without talking to their doctor. If a pharmacy says a drug is out of stock, ask if they can check with other local pharmacies or if the prescriber can switch to an approved alternative. Many hospitals now have digital tools that suggest safe substitutes. Don’t rely on online pharmacies-many sell unverified or expired products during shortages.

Is the U.S. government doing enough to fix drug shortages?

Not yet. The FDA has improved its tracking and emergency import rules, but manufacturers aren’t required to give advance notice of production halts. Congress has proposed bills like the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act and the Drug Supply Chain Security Act reforms, but they’re still stuck in committee. Real change requires forcing manufacturers to diversify supply chains and rewarding U.S.-based production.

What’s Next for Health Systems

The next frontier is predictive modeling combined with local manufacturing. By 2027, health systems with AI-driven forecasting and regional compounding labs will cut drug shortages by 70% compared to 2024 levels. The goal isn’t just to avoid empty shelves-it’s to make sure no patient delays treatment because a pill was made 8,000 miles away and got stuck in customs.

It’s no longer about reacting. It’s about redesigning the entire pipeline-from raw materials to the patient’s hand. The systems that do this best won’t just survive the next shortage. They’ll set the new standard for healthcare reliability.

Elizabeth Grace

December 2, 2025 AT 09:21I cried when my mom couldn’t get her chemo drug last month. Not because I’m weak-because the system is broken. They told us to ‘call back next week.’ Like that’s a solution when someone’s body is falling apart.

Steve Enck

December 2, 2025 AT 10:30While the operational adaptations described are statistically significant, they remain epiphenomenal within the broader ontological framework of neoliberal pharmaceutical capitalism. The root cause-profit-driven fragmentation of essential goods-is not addressed by inventory algorithms or regional compounding labs. These are palliative measures masking systemic decay.

Jay Everett

December 3, 2025 AT 19:04Y’ALL. I work in a hospital pharmacy and let me tell you-this is REAL. We had a week where we were swapping out vancomycin for ceftaroline like it was a game of musical chairs. 😅 But honestly? The AI alerts and robot dispensers? Life savers. We used to spend 3 hours a day playing phone tag with distributors. Now? We get alerts at 3am and fix it before breakfast. 🙌 The system ain’t perfect, but it’s finally fighting back.

मनोज कुमार

December 4, 2025 AT 20:33Joel Deang

December 5, 2025 AT 13:04so like… i just found out my doc’s office uses this Johns Hopkins app to swap drugs? mind blown. 🤯 i had no idea they could just pick a different one that works. and i was scared to ask bc i thought they’d say ‘sorry, no options.’ turns out they’ve got backup plans for almost everything. kinda feels like magic lol

Roger Leiton

December 7, 2025 AT 13:00This is the most hopeful thing I’ve read all year. 🤗 I’ve been a nurse for 12 years and I’ve seen too many patients wait because a pill got stuck in customs. The fact that hospitals are now building their own labs and using AI to predict shortages? That’s not just innovation-that’s dignity. We’re finally treating medicine like a human right, not a commodity. I’m crying happy tears.

Laura Baur

December 8, 2025 AT 05:23It is deeply concerning that the article romanticizes hospital-led manufacturing as a panacea while ignoring the moral hazard it introduces. When healthcare institutions become producers, they inherently distort market signals, discourage private investment in generic manufacturing, and create a dangerous precedent where public health infrastructure is privatized under the guise of resilience. The FDA’s emergency import waivers are ethically dubious-unapproved drugs, even if WHO-compliant, lack the full regulatory scrutiny required for human safety. This is not progress. It is a surrender to chaos dressed in clinical scrubs.

Jack Dao

December 10, 2025 AT 04:38So let me get this straight-we’re letting hospitals build their own drug factories because we couldn’t be bothered to regulate the 2 companies that make 90% of our antibiotics? 🤦♂️ This isn’t innovation. It’s the sound of a society giving up. If we cared about this, we’d have passed the Drug Supply Chain Act in 2020. We didn’t. Now we’re patching holes with $42M labs. Congrats, we’re all engineers now.

dave nevogt

December 10, 2025 AT 23:05I’ve spent the last decade watching this unfold-from the quiet panic in rural ERs to the frantic calls from oncology nurses. What struck me most isn’t the tech or the coalitions. It’s the shift in culture. Pharmacists used to be invisible. Now they’re in the room when treatment plans are made. Nurses are trained to speak up before a script is even written. That’s the real win. Not the robots. Not the AI. It’s that we finally stopped treating the people who keep the system alive as background noise. They’re the ones who noticed the shortage before the inventory system did. And now, finally, they’re being heard.