What Is Nephrotic Syndrome?

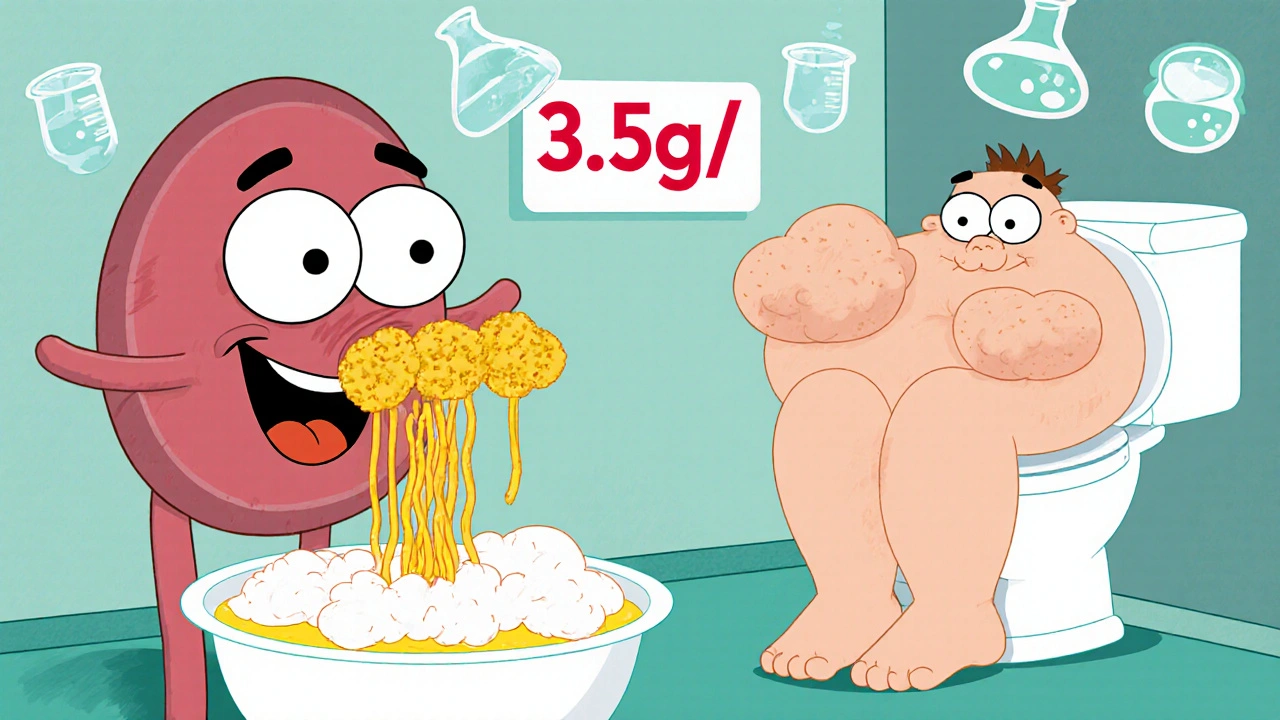

Nephrotic syndrome isn’t a disease on its own-it’s a set of symptoms that tell you something’s wrong with your kidneys. The main signs are heavy proteinuria, swelling (edema), low blood albumin, and high cholesterol. When the filters in your kidneys-called glomeruli-get damaged, they leak large amounts of protein into your urine. This isn’t just a small amount; it’s more than 3.5 grams a day in adults, or over 40 mg/m²/hour in kids. That’s like losing a tablespoon of protein every day through your pee.

This protein loss causes your blood to hold less fluid, so water leaks into your tissues and causes swelling. You might notice puffy eyes in the morning, swollen ankles, or even a bloated belly. Some people gain 10 to 15 pounds in just a few days from fluid buildup alone. It’s not fat-it’s water stuck in the wrong places.

Why Does Protein Leak Into the Urine?

Your kidneys have tiny filters made of cells called podocytes. These cells have finger-like projections that wrap around blood vessels and act like a sieve. Proteins like albumin are too big to pass through-normally. But when the slit diaphragm between these fingers breaks down, proteins slip through. This damage can come from immune attacks, genetic mutations, or long-term stress like diabetes.

In kids, the most common cause is minimal change disease. The glomeruli look normal under a microscope, but they’re not working right. In adults, it’s often focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) or membranous nephropathy. These involve actual scarring or thickening of the filters. Diabetes is another major player-especially in older adults. About 30% of nephrotic syndrome cases in people over 65 are tied to diabetes.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t guess-they measure. The first clue is usually foamy urine, which happens because of all the protein. But you need lab tests to confirm. A 24-hour urine collection is the gold standard: if you’re spilling over 3.5 grams of protein in a day, that’s nephrotic syndrome. Blood tests will show low albumin (under 3.0 g/dL) and high cholesterol, often above 300 mg/dL.

In children, a biopsy isn’t always needed. If they’re under 10, have no other symptoms, and respond quickly to steroids, doctors assume minimal change disease. But in adults, or if steroids don’t work, a kidney biopsy is essential. It tells you whether it’s FSGS, membranous, or something else. This matters because treatment changes based on the cause.

Nephrotic vs. Nephritic Syndrome: What’s the Difference?

People often mix up nephrotic and nephritic syndrome. They both involve kidney damage, but they’re different. Nephrotic syndrome is about protein loss, swelling, and high cholesterol. Nephritic syndrome is about inflammation-blood in the urine, high blood pressure, and reduced kidney function. You’ll see red blood cell casts in the urine with nephritic, not protein-heavy foam.

If you have high blood pressure and dark, cola-colored urine, it’s more likely nephritic. If you’re puffy all over but your urine looks normal except for foam, and your blood pressure is fine, it’s probably nephrotic. Getting this right matters because the treatments are totally different.

What Causes Nephrotic Syndrome in Adults vs. Kids?

Age changes everything. In kids under 6, 80-90% of cases are minimal change disease. It’s mysterious-no infection, no trigger-but steroids fix it in most cases. In teens and adults, it’s more complex. FSGS is the top cause, affecting about 40% of adults. Membranous nephropathy comes next, often linked to autoimmune issues or hepatitis. Diabetes is a big one too, especially in people over 65.

Less common causes include lupus, certain infections like hepatitis B or C, and even some medications like NSAIDs or penicillamine. There’s also a rare genetic form called congenital nephrotic syndrome, caused by mutations in the NPHS1 gene. Babies with this show massive proteinuria in the first three months of life. It’s rare-less than 1% of cases-but it needs a different approach than steroids.

How Is It Treated?

Treatment has two goals: stop the protein leak and prevent complications. The first-line drug for kids is prednisone. Most respond within 2-4 weeks. Dosing is based on body surface area-about 60 mg/m² per day for 4-6 weeks, then slowly tapered over months. In adults, the dose is usually 1 mg/kg per day, capped at 80 mg, for 8-16 weeks.

But not everyone responds. About 10-15% of kids and up to 40% of adults are steroid-resistant. That’s when you switch to calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus or cyclosporine. For FSGS and membranous disease, rituximab is becoming more common. It’s an IV drug that targets immune cells, and studies show it reduces proteinuria in about half of patients who didn’t respond to steroids.

New drugs are on the horizon. Sparsentan, a dual blocker of angiotensin and endothelin, showed a 47.6% drop in proteinuria in a 2022 trial-far better than older blood pressure meds. Budesonide (Tarpeyo), approved for IgA nephropathy, is also being tested in FSGS with promising early results.

Diet and Lifestyle: What You Can Do

Medications help, but your diet matters just as much. Sodium is the enemy. Cutting salt to under 2,000 mg a day can reduce swelling by 30-50% in just 72 hours. That means no processed food, no canned soups, no salty snacks. Read labels-salt hides everywhere.

Protein intake needs balance. Too much protein can stress your kidneys, but too little can make you weak. Aim for 0.8 to 1.0 grams per kilogram of body weight. For a 70 kg adult, that’s about 56-70 grams a day. Good sources are eggs, lean meat, tofu, and dairy.

Cholesterol management is part of treatment too. Statins are often prescribed, even if your cholesterol isn’t sky-high. The goal isn’t just to lower numbers-it’s to protect your blood vessels from damage caused by chronic protein loss.

Watch Out for Complications

Nephrotic syndrome isn’t just about swelling. It raises your risk of blood clots-up to four times higher. The kidneys lose proteins that normally prevent clotting, and your blood gets thicker. Renal vein thrombosis happens in 10-40% of adults with severe hypoalbuminemia (under 2.0 g/dL). That’s why some patients need blood thinners like warfarin or low-molecular-weight heparin.

Infections are another big risk. Losing antibodies in the urine leaves you vulnerable. Kids on steroids often get colds, ear infections, or even pneumonia. That’s why vaccines are critical. You can get flu shots and pneumonia shots during treatment, but never live vaccines like MMR or chickenpox while on high-dose steroids.

Also, watch for sudden weight gain, shortness of breath, or chest pain. These could mean fluid in the lungs or a clot. Don’t wait-call your doctor.

How Do You Know If Treatment Is Working?

Remission isn’t just feeling better-it’s measured. In kids, remission means three days in a row of negative or trace protein on a urine dipstick. Relapse is three days of 2+ or 3+ protein. Parents often miss early relapses because the swelling comes back slowly. Weekly dipstick tests at home help catch it before it gets bad.

Relapses are common. Up to 70% of kids with minimal change disease have at least one relapse, often after a cold or virus. That’s why many doctors keep a short course of steroids at home for emergencies. Adults relapse too, but less predictably. The key is to treat relapses early before protein loss gets extreme.

What’s the Long-Term Outlook?

Prognosis depends on the cause. If it’s minimal change disease, 95% of patients keep their kidney function for at least 10 years. FSGS is tougher-only 50-70% avoid kidney failure over a decade. Membranous nephropathy sits in the middle at 60-80%. But if your proteinuria stays above 1 gram per day despite treatment, your risk of end-stage kidney disease jumps 4.2 times.

Diabetes-related nephrotic syndrome has the worst outlook. Many progress to dialysis within 5-10 years. That’s why controlling blood sugar and blood pressure isn’t optional-it’s survival.

What’s New in Research?

Science is moving fast. The NEPTUNE study found three distinct molecular subtypes of FSGS. One responds to steroids, another to rituximab, and a third doesn’t respond at all. That means one day, we might test your kidney tissue and know exactly which drug to use-no trial and error.

Researchers are also testing drugs that protect podocytes-the cells that keep proteins in. Rho kinase inhibitors, for example, have reduced proteinuria by 60-70% in animal models. Human trials are coming soon.

Genetic testing is now recommended for kids under 1 or with a family history. If it’s a genetic form, steroids won’t help. You avoid unnecessary treatment and focus on supportive care instead.

Is nephrotic syndrome curable?

In many cases, yes-especially in children with minimal change disease. Most go into remission with steroids and stay in remission for years. But it’s not always a one-time fix. Relapses are common, and some forms like FSGS or diabetes-related nephrotic syndrome can lead to permanent kidney damage. The goal is to achieve and maintain remission to protect kidney function long-term.

Can diet alone treat nephrotic syndrome?

No. Diet helps manage symptoms like swelling and high cholesterol, but it doesn’t fix the damaged kidney filters. Medications like steroids or immunosuppressants are needed to reduce proteinuria. A low-salt, balanced-protein diet supports treatment but can’t replace it.

Why do people with nephrotic syndrome get blood clots?

When the kidneys leak large amounts of protein, they also lose anticoagulant proteins like antithrombin. This makes the blood more likely to clot. The risk is highest when serum albumin drops below 2.0 g/dL. Blood clots can form in the legs, lungs, or even the kidney veins themselves, which can cause sudden pain and kidney damage.

Is nephrotic syndrome genetic?

Most cases aren’t. But about 1% are caused by inherited gene mutations, like NPHS1 or NPHS2. These usually show up in infancy or early childhood. Genetic testing is now recommended for babies under 1 year old with nephrotic syndrome or those with a family history. If it’s genetic, steroids won’t work-treatment focuses on managing symptoms and preparing for possible kidney transplant.

Can you live a normal life with nephrotic syndrome?

Yes, many do. Kids with minimal change disease often outgrow it by adolescence. Adults with responsive forms can stay in remission for years with proper treatment. The key is regular monitoring, sticking to meds, watching your salt intake, and treating relapses early. While some may eventually need dialysis, most can live full, active lives with careful management.

Alex Ramos

November 12, 2025 AT 17:09Just had a patient come in with 8g/day proteinuria last week. Kid was 7, no history, just puffy eyes. Steroids hit like a miracle-protein gone in 10 days. Minimal change disease is wild how fast it responds. Still blows my mind.

Also, don’t skip the sodium restriction. One kid I had ate a whole bag of chips after diagnosis. Swelling came back worse than before. Diet isn’t optional-it’s part of the med regimen.

Alyssa Lopez

November 13, 2025 AT 03:23Proteinuria >3.5g/day = nephrotic. Got it. But why do docs still use 24hr urine collections? We got dipsticks that read protein/creatinine ratio now. Way faster. And way less annoying for kids who have to pee in a bucket for a day. American medicine still stuck in the 90s.

Also, statins? For nephrotic? Bro. The cholesterol is a *symptom*, not the problem. Fix the leak, the lipids fix themselves. Stop treating markers and treat the disease.

Erica Cruz

November 13, 2025 AT 10:33Wow. So much jargon. Like, who even reads this? Just say ‘kidneys leaking protein’ and ‘take steroids’. No one needs to know about podocytes or slit diaphragms. This feels like a med student’s term paper. Why are we giving this to patients? It’s overwhelming.

Also, ‘Sparsentan’? Sounds like a new energy drink. Next thing you know, Big Pharma will sell us ‘NephroBoost™’ in vending machines.

Chrisna Bronkhorst

November 15, 2025 AT 00:11Diabetes causes 30% of nephrotic in over 65? That’s not a coincidence. That’s a failure. We let people eat sugar like it’s candy and then act shocked when their kidneys melt. This isn’t medicine. It’s triage after negligence.

Also, why is everyone still using prednisone? It’s 2025. We have targeted immunotherapies. But nope. Let’s keep flooding people with steroids and calling it ‘standard of care’.

Amie Wilde

November 16, 2025 AT 06:25My cousin had this. Swelling so bad she couldn’t see her toes. Took 3 months to get a diagnosis. Doctors kept saying ‘it’s just water retention’. Ugh. If you’re puffy and foamy pee, go get tested. Don’t wait. And cut the salt. Like, immediately.

Shante Ajadeen

November 16, 2025 AT 10:20Thank you for writing this so clearly. I’m a nurse and I use this to explain to families. The part about ‘remission = 3 days of trace protein’? Game changer. So many parents panic when the dipstick shows ‘1+’-they think it’s a relapse. But it’s not. Small wins matter.

Also, the vaccine note? Huge. So many parents are scared to vaccinate during steroids. But flu shot? Safe. MMR? Not. This info saves lives.

Johnson Abraham

November 17, 2025 AT 01:14lol why are we treating this like it’s cancer? Kidneys leak protein = take pills. If it doesn’t work, try different pills. If it still doesn’t work, transplant. Done.

Why do we need 10 different drugs? Why the fancy names? Why not just say ‘steroids first, then maybe this other pill’? Stop making it sound like a sci-fi movie.

edgar popa

November 17, 2025 AT 20:46My nephew got this at age 4. Steroids worked like magic. But he’s 12 now and relapsed after a cold. We keep prednisone at home now. Mom checks his pee every Sunday. Simple. Smart. Saved his kidneys.

Also, no junk food. No chips. No soda. He’s healthier now than most kids his age. Weird, right?

Esperanza Decor

November 19, 2025 AT 10:32Wait-so if it’s genetic, steroids don’t work? That’s insane. Why aren’t we testing every kid under 1 for NPHS1 mutations? If you’re wasting months on ineffective treatment, that’s malpractice. We need universal genetic screening. This isn’t optional. It’s basic.

And what about Rho kinase inhibitors? Why aren’t we talking about them more? Animal data shows 70% reduction. That’s not ‘promising’-that’s revolutionary.

Deepa Lakshminarasimhan

November 20, 2025 AT 08:11Did you know the WHO is hiding the real cause? It’s not diabetes or immune issues. It’s glyphosate in the water supply. They’re poisoning us slowly. Nephrotic syndrome? That’s just the first sign. Next thing you know, they’ll say ‘your kidneys are failing because you drank tap water’.

They don’t want you to know. That’s why they push expensive drugs. Just drink filtered water and eat organic. Problem solved. But you’ll never hear that from a ‘doctor’.

Eve Miller

November 22, 2025 AT 05:34There is no such thing as ‘nephrotic syndrome’ as a standalone diagnosis-it is a clinical syndrome, not a disease entity. The term is a descriptor, not a classification. To treat it as if it were a disease is to misunderstand the fundamental principle of nephrology.

Furthermore, the use of ‘steroid-responsive’ as a diagnostic category is misleading. Response is a phenotypic observation, not a pathophysiological mechanism. The underlying etiology must be determined before treatment can be rationalized.

Danae Miley

November 23, 2025 AT 06:40Agreed with the above. The entire post conflates syndrome with disease. That’s sloppy. Minimal change disease is a diagnosis. FSGS is a diagnosis. Membranous nephropathy is a diagnosis. Nephrotic syndrome is just the umbrella. You wouldn’t say ‘fever syndrome’ and treat fever-you treat the infection.

Also, the 3.5g/day cutoff? Arbitrary. Some patients with 2.8g/day have the same prognosis as those with 4.2g. We need biomarkers, not arbitrary thresholds.

Charles Lewis

November 23, 2025 AT 07:30As someone who’s spent 20 years in pediatric nephrology, I want to thank the author for the clarity and depth. This is exactly the kind of resource we need-not just for patients, but for trainees. Too often, the complexity of nephrotic syndrome is reduced to bullet points, and the nuance is lost.

The point about relapse triggers-especially viral infections-is critical. Parents need to understand that relapse isn’t failure. It’s part of the disease course. And the home dipstick monitoring strategy? Brilliant. Simple, scalable, life-changing.

I’ve seen too many families lose faith because they didn’t understand the difference between remission and cure. This post helps bridge that gap. Please keep writing. We need more of this.

Gary Hattis

November 24, 2025 AT 11:15Just came back from a trip to India. Saw a 6-year-old with nephrotic syndrome in a rural clinic. No steroids. No labs. Just salt restriction and a prayer. He was swelling, but alive. No one had heard of rituximab. No one knew what FSGS was.

But guess what? He was doing better than half the kids I’ve seen in U.S. hospitals-because his mom cut out the salt, kept him hydrated, and never let him eat processed food.

Medicine isn’t just about drugs. It’s about access, culture, and dignity. We’re so focused on the latest drug trial, we forget that sometimes, the best treatment is a mother who knows how to read a food label.

dace yates

November 26, 2025 AT 01:56Wait-so if someone has genetic nephrotic syndrome, they can’t get a kidney transplant? Or is that just if it’s congenital? I’m confused. Does the mutation affect the new kidney too? Or is it only in the original one? Someone explain please. I want to understand.