When you have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-whether it’s Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis-and you’re thinking about getting pregnant, the biggest question isn’t just can I get pregnant? It’s can I stay safe-for you and your baby. The truth is, most women with IBD have healthy pregnancies and healthy babies. But only if their disease is under control and they’re on the right medications. Stopping your meds out of fear can be riskier than taking them.

Uncontrolled IBD Is the Real Threat

Let’s clear up a dangerous myth first: the medications themselves aren’t the biggest danger during pregnancy. It’s the disease. If your IBD is active when you conceive-or flares up during pregnancy-you’re looking at much higher risks. Studies show women with active IBD at conception are 2.3 times more likely to have a preterm baby, 1.8 times more likely to have a low-birth-weight baby, and 1.6 times more likely to experience stillbirth compared to those in remission. That’s not a small risk. That’s the kind of risk that changes outcomes.

And here’s the thing-when IBD flares, your body is under stress. Inflammation doesn’t just hurt your gut. It affects your placenta, your blood flow, your hormone balance. It can trigger early labor. It can reduce nutrient delivery to your baby. Medications, when chosen correctly, help you avoid this. The goal isn’t to be completely medication-free. It’s to be disease-free while staying on safe drugs.

Medications That Are Safe to Keep Taking

There are several IBD medications that have been tracked through thousands of pregnancies-and the data is reassuring.

Aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) like mesalamine and sulfasalazine are considered safe throughout pregnancy. The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) both say you should keep taking them. But here’s the catch: not all mesalamine brands are the same. Some, like Asacol HD, use a coating called dibutyl phthalate (DBP). Animal studies and human case reports link DBP to urogenital birth defects in male babies. So if you’re on Asacol HD, talk to your doctor about switching to Lialda, Delzicol, or Apriso-formulations that don’t contain DBP. You don’t need to stop your treatment. You just need the right version.

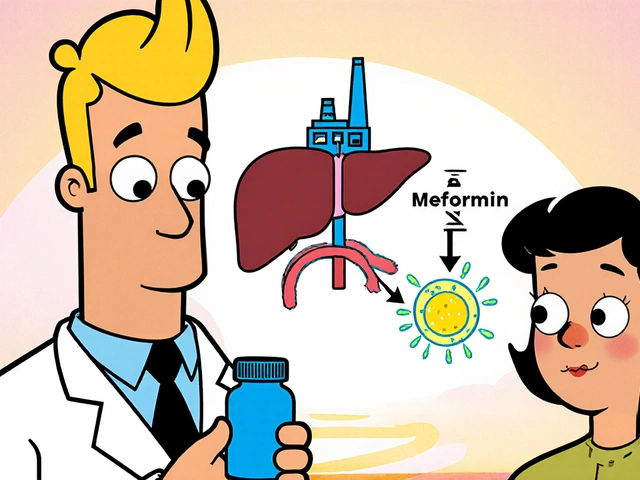

Anti-TNF drugs like infliximab (Remicade) and adalimumab (Humira) are among the best-studied biologics in pregnancy. The PIANO registry, which followed over 2,000 pregnancies, found no increase in birth defects compared to the general population. These drugs are safe to continue through delivery. Some doctors may adjust the timing of your last dose in the third trimester to reduce how much passes to the baby-but that’s a decision based on your individual situation, not a blanket rule.

Vedolizumab (Entyvio) is newer, but data from 100+ pregnancies shows no increase in birth defects or serious infections in babies. One early study showed fewer live births in the vedolizumab group-but when researchers looked closer, the difference disappeared in women whose IBD was under control. That tells you something important: it’s not the drug. It’s the disease.

Ustekinumab (Stelara) is also now well-supported by data. Over 680 pregnancies have been tracked, and outcomes match those of the general population. Even women who received induction doses (the first few shots) during pregnancy didn’t show higher risks. This is a solid option if you’re switching from an anti-TNF or haven’t responded to one.

Medications to Stop Before Pregnancy

Some drugs are clear no-gos during pregnancy. Don’t wait until you’re pregnant to find out.

Methotrexate is a known teratogen. It causes major birth defects in 17-27% of exposed pregnancies. It’s not a risk you take lightly. You need to stop it at least 3-6 months before trying to conceive. Same goes for thalidomide-a drug so dangerous it’s banned in pregnancy worldwide.

JAK inhibitors like tofacitinib (Xeljanz) and upadacitinib (Rinvoq) are trickier. There’s limited data-only about 11 pregnancies for tofacitinib, and 98 for upadacitinib. No red flags yet, but because these drugs affect the JAK-STAT pathway-which is crucial for early embryo development-guidelines recommend stopping them 4-6 weeks before conception if you have other options. It’s a precaution, not a panic. But you need to plan ahead.

Corticosteroids like prednisone are often used to control flares, but they’re not ideal in early pregnancy. Studies link first-trimester use to a 1.4-2.3 times higher risk of cleft lip or palate. If you’re on steroids, work with your doctor to get off them before conception-or switch to a safer long-term medication.

What About Breastfeeding?

Yes, you can breastfeed while on most IBD medications. Anti-TNFs, vedolizumab, and ustekinumab pass into breast milk in tiny, clinically insignificant amounts. The ECCO guidelines say it’s safe. Even sulfasalazine is considered low-risk-though some doctors still recommend watching your baby for unusual fussiness or diarrhea, just in case.

One thing to remember: if you’re on a JAK inhibitor, you should wait at least 24 hours after your last dose before breastfeeding. That’s the standard precaution.

Planning Ahead: Timing Matters

The best time to optimize your IBD treatment is before you get pregnant. Not when you find out you’re pregnant. Not when you’re in the middle of a flare. Three to six months before conception is the sweet spot.

Why? Because you need time to:

- Get your IBD into remission (ideally confirmed by endoscopy, not just symptoms)

- Switch medications if needed (like swapping DBP-containing mesalamine for a safer version)

- Start or adjust folate supplements (especially if you’re on sulfasalazine)

- Coordinate care between your gastroenterologist and OB-GYN

Many women don’t realize their IBD is a pregnancy risk factor. That’s why only 42% of community gastroenterologists correctly identify all safe medications. Don’t assume your doctor knows. Bring the guidelines. Ask about the PIANO registry. Ask if your meds are Category A (safe with strong data) or Category C (stop before conception).

What About Your Baby After Birth?

Good news: babies exposed to IBD medications in utero can get all their routine vaccines on schedule-including live vaccines like MMR and varicella. There’s no evidence these vaccines are unsafe for infants whose moms took anti-TNFs, vedolizumab, or ustekinumab during pregnancy. The ECCO guidelines confirm this. You don’t need to delay immunizations.

Long-term studies are still tracking these children. The PIANO registry is following kids up to age 10. Early data shows no increased risk of developmental delays, infections, or cancer. That’s reassuring.

What If You Get Pregnant Unexpectedly?

If you’re on a safe medication-mesalamine (DBP-free), anti-TNFs, vedolizumab, or ustekinumab-keep taking it. Don’t stop. Call your doctor right away. If you’re on methotrexate or a JAK inhibitor, stop immediately and contact your gastroenterologist. They’ll help you transition safely.

Don’t blame yourself. Unexpected pregnancies happen. The goal now is to protect your baby from the biggest threat: uncontrolled IBD.

Bottom Line: Stay in Control, Stay Safe

Having IBD doesn’t mean you can’t have a healthy pregnancy. It means you need a better plan. The data is clear: staying on safe medications keeps you in remission, and remission keeps your baby safe. The risks from active disease far outweigh the risks from the right drugs.

Work with your team. Ask questions. Demand clarity. Bring the latest guidelines. You’re not just managing a chronic illness-you’re protecting a life. And you have the tools to do it right.

Chrisna Bronkhorst

November 11, 2025 AT 23:02Stop scaring people with stats without context. Yes, active IBD is bad but so is being on 5 different biologics by 30. My sister had 3 flares in 2 years on Humira and still had a healthy baby. The real issue is doctors pushing meds like they’re candy. You don’t need to be on anything if you’re in remission with diet and lifestyle. The data cherry-picks the ones who stayed on drugs. What about the ones who went drug-free and did fine?

Amie Wilde

November 13, 2025 AT 02:14Asacol HD has DBP? I had no idea. Switched to Lialda last month. So glad I read this before getting pregnant. Thanks for the heads up.

Gary Hattis

November 14, 2025 AT 00:28Let’s be real - this post is basically a pharma pamphlet dressed up as medical advice. Anti-TNFs are safe? Sure, if you ignore the 2023 Lancet study showing higher rates of childhood autoimmune disorders in kids exposed to infliximab. And who’s tracking these kids beyond age 5? The PIANO registry? That’s funded by Janssen. Don’t get me wrong - I’m not saying meds are evil. But we’re treating pregnancy like a lab experiment. You’re not just protecting your baby from IBD. You’re exposing them to a cocktail of synthetic molecules with unknown long-term effects. The real threat isn’t inflammation - it’s overmedicalization.

Esperanza Decor

November 14, 2025 AT 13:21I’m 3 months pregnant and on Humira. I was terrified to keep taking it until I read the PIANO data. My GI and OB both said it’s fine. I also switched from Asacol HD to Delzicol - no way was I risking my baby’s genitals over a brand name. Folate is now my new best friend. If you’re planning pregnancy and have IBD - don’t panic. Just plan. Talk to your team. Bring this article to your next appointment. You got this.

Deepa Lakshminarasimhan

November 14, 2025 AT 21:06They’re lying about the meds being safe. All these drugs mess with your immune system. Babies born to moms on biologics are more likely to get sick later. Why? Because their immune systems were trained in a lab, not in nature. And who’s paying for all these studies? Big Pharma. They want you to stay on drugs forever. Even the FDA knows. That’s why they put black box warnings on everything. They just don’t tell you when you’re trying to get pregnant.

Erica Cruz

November 14, 2025 AT 23:42Oh wow. Another ‘trust your doctor’ piece from someone who clearly has never had to navigate this alone. Let me guess - you’re a gastroenterologist with a sponsored blog. Methotrexate = bad. JAK inhibitors = maybe bad. But biologics? Totally fine. Convenient. Also, ‘switch to Lialda’? Did you check the price? Most people can’t afford that. And ‘bring the guidelines’? Yeah, right. My insurance won’t cover the consult. This is performative medicine for the privileged. Real talk: if you’re poor, you’re screwed.

Johnson Abraham

November 15, 2025 AT 16:56so like… if u got crohns and wanna get preggo just dont stop ur meds unless its methotrexate? lol ok. i thought u had to go all natural or something. also why is asacol bad? i thought it was just a fancy pill. anyway im taking humira and im preggo and my baby is fine so far. 🤞

Shante Ajadeen

November 16, 2025 AT 18:26This is exactly what I needed to read. I was so scared to keep taking my meds but now I feel like I can breathe again. I switched to Apriso last month and started taking prenatal vitamins with extra folate. My GI doc and OB are on the same page now. It’s scary to be pregnant with IBD, but you’re not alone. If you’re reading this and feeling overwhelmed - reach out. There are groups for this. You’re doing better than you think.